“Be special, give sperm” is the slogan of Britain’s largest sperm bank. However, it seems not everyone is suitable for this elite group of special sperm givers. The Guardian ran an article a couple of weeks ago on the ‘eugenic’ nature of the London Sperm Bank, which described “a policy of turning away autistic donors and those diagnosed with other neurological disabilities, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], dyslexia and obsessive compulsive disorder.” What are the practical implications of such policies? Should there be legislation to prevent it? Is this ‘political correctness gone mad’ or our old ‘ally’ eugenics rearing its ugly head?

‘Be special, give sperm’ – London Underground ad

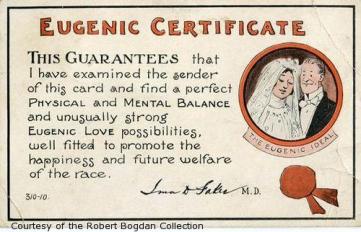

Measures against ‘genetic’ disease will always be associated with eugenics. That’s fair enough. In mid-twentieth century Britain, artificial insemination was put forward by eugenicist Herbert Brewer as a rational and efficient means of selective breeding. If used as the sole means of reproduction, it could at once ensure that the ‘fit’ were selected as donors and that the ‘unfit’ were ‘weeded out’. As a natural progression from late-nineteenth century Social Darwinism, eugenicists believed such techniques could be used to consciously guide human evolution. Artificial insemination was seen as a ‘humane’ alternative to negative eugenics e.g. the sterilization of hereditary ‘mental defectives’. Though such policies are largely associated with Nazi Germany and many US states, they were also taken into consideration by leading experts within the British Eugenics Society. According to Brewer, artificial insemination would “transform the problem of negative eugenics.” With regard to the prevalence of mental deficiency and other ‘latent’ defects, whereas “the elimination of such degeneracy by sterilizing” would be like “clearing a river of fish by catching the few which jump from the water,” artificial insemination would ensure that the “existence of the whole inextricable tangle of latent defect” would be swept out “in a few generations, replacing it concurrently with hereditary material of the highest excellence.”

Certainly after the Holocaust, sterilization was a no-go area for eugenicists. In 1950, the Eugenics Society secretary, Carlos Blacker described artificial insemination as having been “successfully used in cases when the male partner is at fault and also when, because of hereditary infirmities in himself or his family, he does not want children of his own.” It is often forgotten that Britain has this ‘eugenic’ past. In fact, the ‘runs in the family’/‘like-produces-like’ understanding of mental disorder was widely accepted in society. The Anglican Church even formed a committee to discuss the moral implications of artificial insemination. Having served on the committee along with Archbishop Fisher, the Bishops of Derby and Oxford and Carlos Blacker, Bishop Barnes of Birmingham was “convinced that artificial insemination, even by a donor, would be an inevitable and perhaps a desirable element in positive genetic engineering” and that soon a time would come “when the greatest geneticist will be accepted as one of the leading agents of Christian progress.” Thus, when artificial insemination was first ‘taking off’ many influential people, not to mention moral pillars of the community, were considering its eugenic benefits. Should we be surprised, then, that the legacy continues with Britain’s largest sperm bank ‘protecting’ future generations from disease?

Notably, the origins of such conditions are unclear and how we diagnose and define them varies greatly. Arguably, they are complex and multifactorial, as much to do with upbringing, life events and the epigenetic impact of the environment on gene behaviour as they are with what ‘runs in the family’. The policy is about as good an idea as the government using programmes of sterilization and euthanasia to try and prevent the spread of ‘feeble-mindedness’ – a catchall term from the early twentieth century based on biological determinism, which connected low IQ with heredity – in society (e.g. Germany, America, Scandinavia, Canada etc). In some countries, this went on until the 1970s! I’m looking at you, Sweden. In any case, other than possible ‘epigenetic trauma’, neither would have a noticeable impact on the genetic health of future populations.

If it were possible, is it even desirable to remove conditions like autism from the population? On behalf of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, Ari Ne’eman argues that “although some evidence suggests eliminating autism, dyslexia and other similar disabilities might remove valuable talents, along with impairments, this is not the primary reason to oppose the emerging eugenics. […] Many individuals who are today diagnosed with learning difficulties or intellectual disabilities would not have been considered such in a society before universal literacy, for example. Tomorrow’s social and technological progress may lead to still new disabilities, demonstrating that the quest to eliminate disability will always be a moving target. Such changes may leave humanity less equal, less diverse, and perhaps even less human.”

Can we call the policies of the London Sperm Bank ‘eugenic’ in intent? If so, should some form of state intervention put an end to it? Ne’eman concludes that “Regulators worldwide should curb eugenic practices. New instruments in international law may be necessary to ensure that ‘designer babies’ do not gain a national home, sparking medical tourism.” The UK government’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority are already investigating the sperm bank as we speak (or as I write/you read). Along with humanity’s shared chequered past regarding elimination and selective breeding, the subjective nature of our understanding of ‘disability’ is perhaps warning enough.

References

Herbert Brewer, ‘Eutelegenesis,’ The Eugenics Review 27, 2 (July 1935), 121.

‘Committee on Artificial Insemination: Draft Interim Report,’ (est. July 1945), The Papers of Ernest William Barnes, Special Collections Library, University of Birmingham, EWB 9/21/28.

Carlos P. Blacker, Statement of Objects (London: Eugenics Society, 1950), 8.

John Barnes, Ahead of His Age: Bishop Barnes of Birmingham (London: Collins, 1979).

Ari Ne’eman, ‘Screening sperm donors for autism? As an autistic person, I know that’s the road to eugenics’, The Guardian (30 December 2015), [http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/dec/30/screening-sperm-donors-autism-autistic-eugenics].

![‘How Designer Children Work’, [http://science.howstuffworks.com/life/genetic/designer-children2.htm]](https://eugenicspastpresentandfuture.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/pgd.gif?w=367&h=595)